What would we do?

Summary

The worst could happen at Waikawa Beach — we could be flooded and isolated. Here’s why that’s now an actual possibility, even if, with any luck, remote, and some questions that arise.

What can you contribute in response to this article?

Intro

In February 2023 we’ve seen the unthinkable in the northern and eastern parts of the North island: flooding, landslips, roads and houses washed away, and loss of life. More than a few communities have been cut off and lost power and cell coverage. Some communities are experiencing more severe weather before they’ve even cleaned up from the last lot.

As I start to write this, 10 days after the cyclone, hundreds of cut-off residents in the West Auckland settlement of Karekare are still without power or road access.

Cyclone Gabrielle that caused such devastation has been called “New Zealand’s worst weather event this century”.

There is nothing to say such an event won’t happen again, and it could even happen to us. It behoves us to look into this a little, even while we hope we will never be the community who are isolated and powerless.

Our history of big storms

The NZ Historic Weather Events Catalogue makes for sobering reading. It shows that Cyclones and severe storms are no strangers to our patch of the world. At random several of the many events:

- March 1880: At Foxton a house was seen rolling down the river.

- July 1956: There was serious flooding in the Wairarapa, lower Manawatu and Hawke’s Bay.

- April 1968 Ex-tropical Cyclone Giselle sank the Wahine. High Wind / Gust at Levin: Three people were injured when a car was whipped off the highway at Levin.

- October 2003 Storm: A cargo plane travelling from Christchurch to Palmerston North was caught in the storm over the Kapiti Coast and vanished from radars northwest of Waikanae Beach. Debris from the plane later washed up. Paekakariki experienced torrential rain and gale force winds, followed by major flooding and landslides.

- January 2008: Flooding at Waikawa Beach: Waikawa Beach was cut off from State Highway 1 when the access road was closed at about 2pm on the 8th. The road was closed overnight.

- February 2018 Ex Tropical Cyclone Gita: this was the one that severely eroded the Miratana block and surrounds at Waikawa Beach.

Storms and cyclones may bring high seas, heavy rainfall at the beach or washing down in the river from the Tararuas, gales. If we’re unlucky it could be the case that we get a bit of everything all at the same time.

We’re in a low-lying area

We’ve seen it before: flooding at the corner of Emma Drive, flooding on Hank Edwards Reserve, flooding across Strathnaver Drive, flooding across Waikawa Beach Road. The paddocks beside the river routinely flood when there’s been a decent amount of rain.

The river rises and floods the low area north of the river, below the footbridge, especially when the tide is also high. The owners of properties beside the river keep an anxious eye on tides and rainfall. In July 2016 a friend asked me to check her Drake Street property as the river was so unusually high.

We’ve seen the water table rise and stay high more than once, most recently in the last 12 months. Folks in the village worried about their septic tanks not emptying properly. The sides of roads filled with water, various properties found their lower areas or driveways turning into ponds. And it lasted for months.

You only need to look around to see that the area between SH1 and the coast around here is mainly flat.

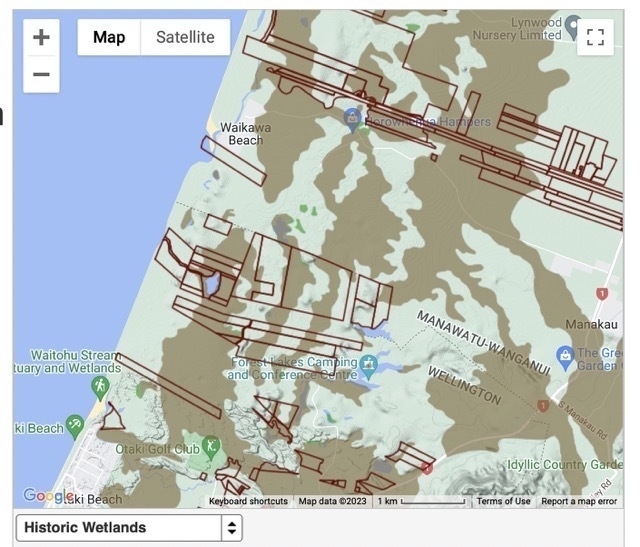

It’s also largely historic swamp, and we see that most clearly when some bits of land turn into ponds after heavy rain.

When we turn on the Historic Wetlands layer on the Visualizing Māori Land maps we see that 50–75% of the map is highlighted as wetland, including most of Waikawa Beach Road. The Soil Drainage layer shows a great deal of the area has Imperfect, Poor or Very Poor drainage.

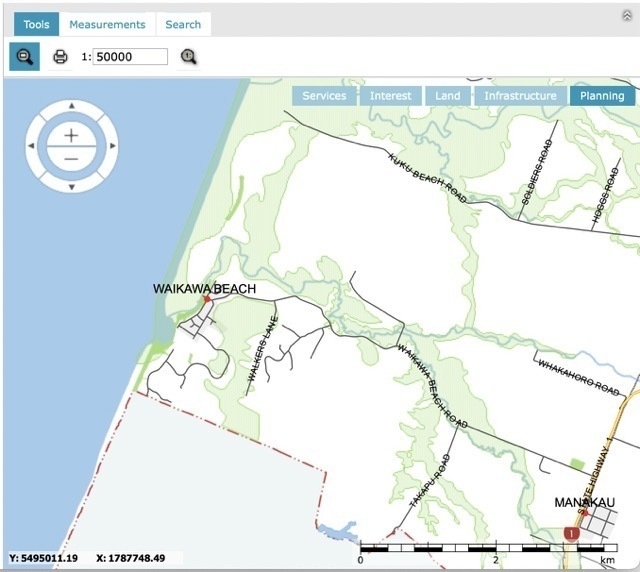

The Horowhenua District Council official mapping tool shows us areas of flood hazard — all along the river. Every time you drive along Waikawa Beach Road you notice that the road pretty much follows the river, which means that most of the road is in the flood hazard area.

That flood hazard area extends into and merges with the Coastal Flood Hazard area along the seaward side of Reay Mackay Grove. There’s also the large flood risk area roughly between Walkers Lane and the village and extending south to the boundary with Kāpiti.

Our tsunami risk

Who can forget the horrifying videos of the 2011 Tōhoku post-quake tsunami in Japan or the post-eruption Tonga tsunami in January 2022?

The Chile tsunami of 23 May 1960 was “observed at locations on the west coast of the North Island … as far south as Whanganui and Paremata, but not at New Plymouth, Foxton, or Himatangi Beach.”

When it came to the tsunami caused by the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano on 15 January 2022, the scientists had problems because of a cyclone going on at the same time:

the concurrent arrival of Cyclone Cody in the north of New Zealand made it difficult to interpret data from our coastal tsunami gauges

Locals spotted the surge coming up the Waikawa River though.

If a sizeable tsunami were to hit our coast it would sweep up the Waikawa river and Waiorongomai Stream and through any breaks in the dunes, or low-lying areas on the foreshore.

That could see it washing into Reay Mackay Grove from the north and south ends, and into the lower lying properties near the river in the village — Hank Edwards Reserve, for example.

If a tsunami travelled far up the river it could well flood quite a large area.

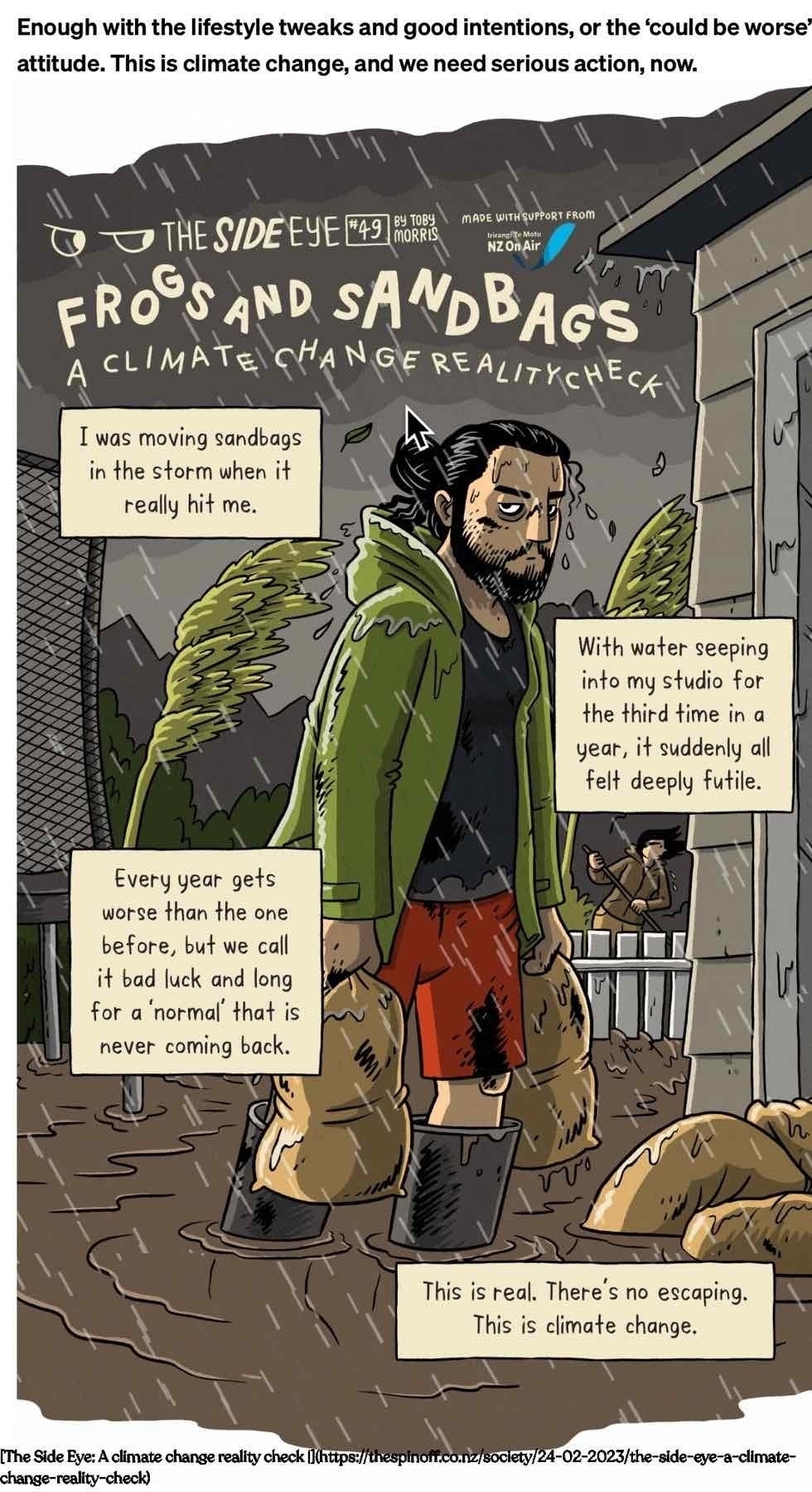

Climate change

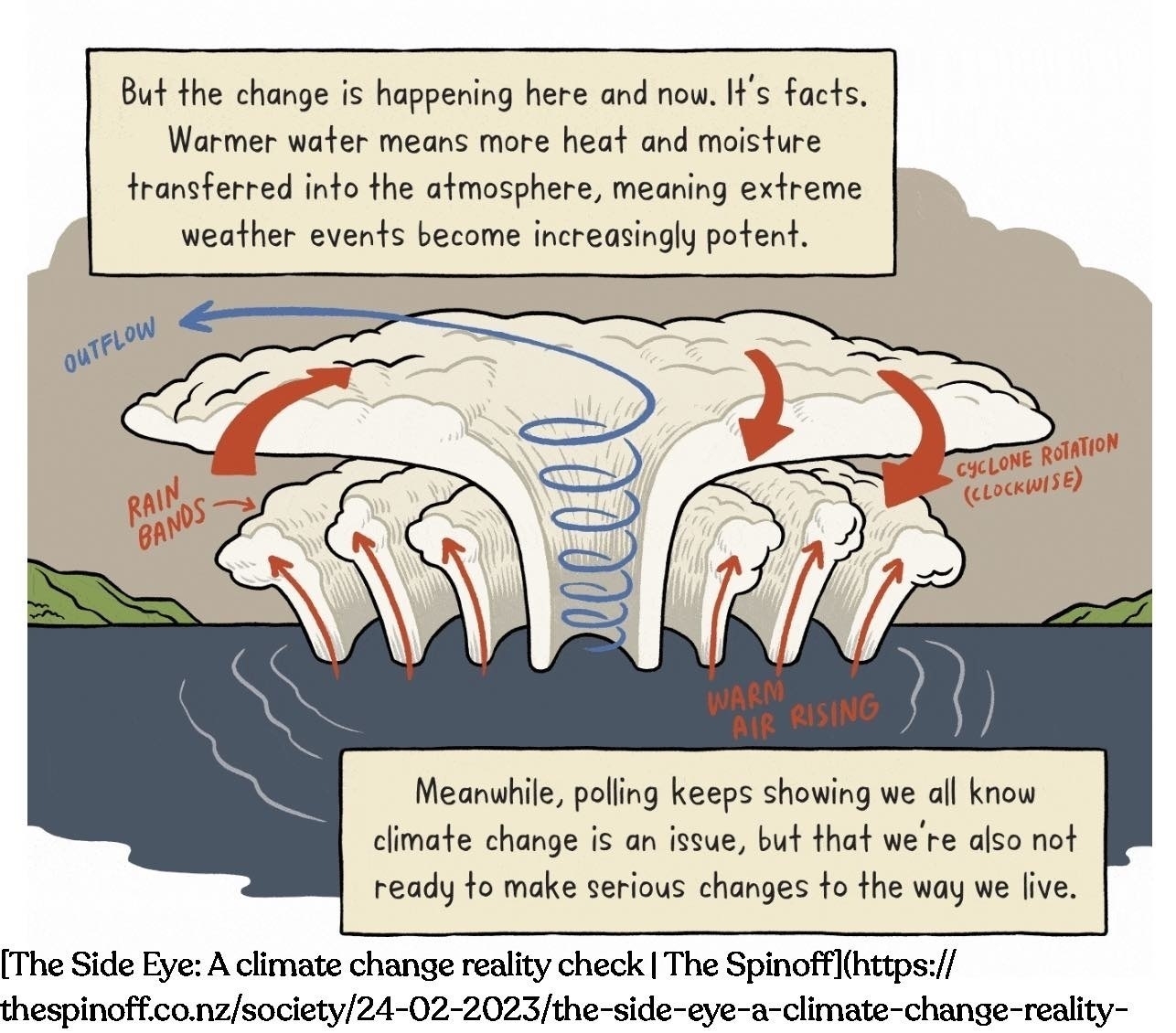

We know the climate is changing and the effects are already apparent.

Sea levels are rising (meaning rivers like ours with a low fall might have more trouble emptying), and the temperature is warming in our part of the world. On 17 January 2023 NIWA said:

It’s official - last year was once again Aotearoa’s warmest on record, knocking 2021 off the top spot. It was also the 8th most unusually wet year on record – meaning lots of rain fell in unusual places.

Warm air holds more moisture, so more rain can fall. Add that to slower moving storms and rainfall in an individual spot may be greater than it used to be on average.

The Washington Post in 2018 pointed out that:

The globe’s hurricanes have seen a striking slowdown in their speed of movement across landscapes and seascapes over the past 65 years, a finding that suggests rising rainfall and storm-surge risks …

Slower-moving storms will rain more over a given area, batter that area longer with their winds and pile up more water ahead of them as they approach shorelines, said Jim Kossin, a scientist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the study’s author.

…it is expected that hurricanes will rain about 7 to 10 percent more per degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) of warming, as the atmosphere retains more water vapor

On 10 October 2017 Horowhenua District Council said:

Figures from our rain gauge show that Horowhenua has had 50% more rainfall over the past few months, compared to the same period last year and 141% more than in 2015 over the same time.

Soil contains air gaps which fill with water when it rains. When the soil reaches 100% saturation it cannot take any more water, this is why we are seeing surface flooding and ponding water.

Only one road in

We’ve seen in Hawke’s Bay, Auckland and Coromandel what disasters can happen when things pile up. History shows us that storms and cyclones can affect more than just the north of our country.

If Waikawa Beach were to experience a slow moving storm dropping an unusually high amount of rain, perhaps combined with unusually high tides on the top of already saturated ground we could find the river floods all the way across Waikawa Beach Road. A bad enough flood could even rip up the road.

In such circumstances some properties may be flooded, forcing people to evacuate.

Add to that disaster the possibility that trees, power lines and maybe cell towers could be brought down by gale force winds. In such a worst case we could be a community that’s cut off as some smaller communities elsewhere have been with Cyclone Gabrielle.

It probably won’t happen. But that’s also what those communities isolated by Cyclone Gabrielle undoubtedly thought.

What say it does happen?

The bright lights

Waikawa Beach doesn’t rely on a town water supply. Most of us have our own water tanks. If it rained enough to cause floods then those tanks would probably all be full. Even if power’s cut so the pumps don’t work, some of us can access the water by bucket if need be.

We’re also a community where a large number of people own tractors, quad bikes, chainsaws and other such useful equipment. More than a few have generators. There are plenty of boats around. We have people with all kinds of useful skills in our community.

Planning measures

This section has questions, not answers. I think it’s worth the community considering what we would need in the worst case.

Let’s imagine the worst has happened: we’re flooded, isolated and don’t have power or cellphone coverage.

How would we communicate with the outside world? Would we all do our own thing or would we find a way to organise ourselves as a whole community to look after one another?

Would we expect the officers of the Waikawa Beach Ratepayers Association to step in and find a way to contact the outside world, to make sure everyone was accounted for and safe? Is that a reasonable expectation?

Should we as a community find someone to be a Safety Liaison or similar? That person might pre-emptively build and maintain contacts with Civil Defence, Horowhenua District Council and others. Maybe in an emergency they’d have access to the various address databases the WBRA holds?

Perhaps they’d have a few supplies they could access if needed, such as a good transistor radio, the codes for the Defibrillator, a community owned generator and fuel (or a list of who already has a generator)? Are there communication options like maybe CB radio that could be used in an emergency? (I don’t know — I have no expertise in Civil Defence.)

There would very likely be other useful equipment they would need too.

Such a person would have contact lists for Council and other authorities, perhaps some basic training. They would know what expertise we have locally and who to call on — doctors, nurses, mental health workers, electricians, plumbers…

The kit would need to be stored somewhere — probably not in the facilities block at Hank Edwards Reserve as in a big enough flood that would be drowned too. Witness the flooding on the Reserve in a big storm in June 2022 and how the water pools nearby after a heavy rain.

Are there things we need to consider for the HDC Annual Plan or for Horizons Regional Council OnePlan? What might they be? Should we discuss any issues connected with this with our local Councillors?

What can you contribute in response to this article?

Links

Intro

History

- Cyclone Gabrielle: Stronger than Bola? New analysis shows how Gabrielle compares - NZ Herald

- New Zealand Historic Weather Events Catalogue: a catalogue of major weather events in New Zealand over the last 200 years from the 1800s to the present, when significant damage or casualties occurred.

- March 1880 Manawatu-Wanganui and Wellington Flooding

- July 1956 North Island Flooding

- April 1968 New Zealand Ex-tropical Cyclone Giselle

- October 2003 New Zealand Storm

- January 2008 Manawatu-Wanganui and Wellington Flooding

- February 2018 Ex Tropical Cyclone Gita

Low-lying area

- Visualizing Māori Land

- HDC Mapping Tool 1:50,000 Planning layer - Flood Hazard

Tsunami

- Rare Video: Japan Tsunami | National Geographic

- GeoNet: Tsunami Stories

- Tonga tsunami: Powerful moment tidal wave hits the Pacific island

- GeoNet: Chile tsunami, 23 May 1960

- GeoNet: Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano tsunami, 15 January 2022

Climate change

- NIWA’s 2022 Annual Climate Summary is now out. | NIWA

- How might slower and wetter storms affect Waikawa Beach?

- The Side Eye: A climate change reality check | The Spinoff

- Preparatory works started to remedy issue at Foxton Cemetery - Horowhenua District Council

Planning measures

Update, 04 March 2023, remember to check the Interactive Coastal Risk Screening Tool which shows that at current levels of activity with regard to climate change the village could be cut off by flood waters.